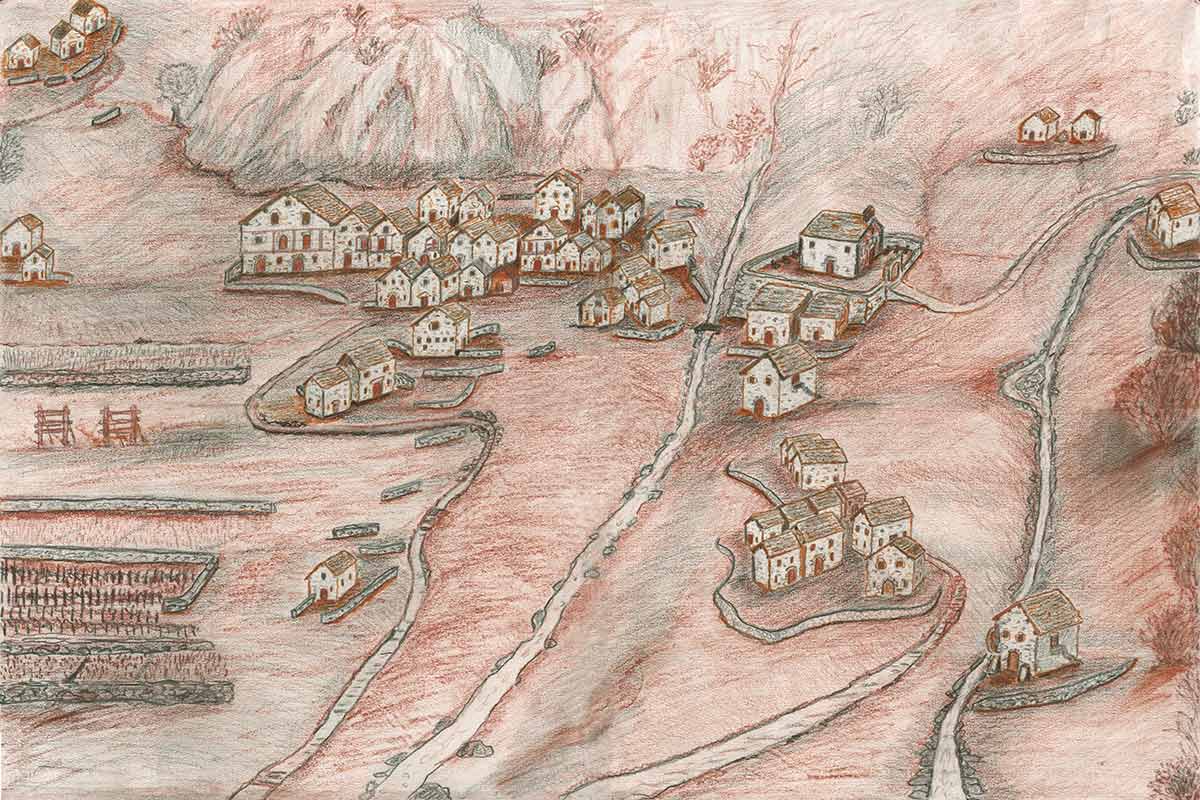

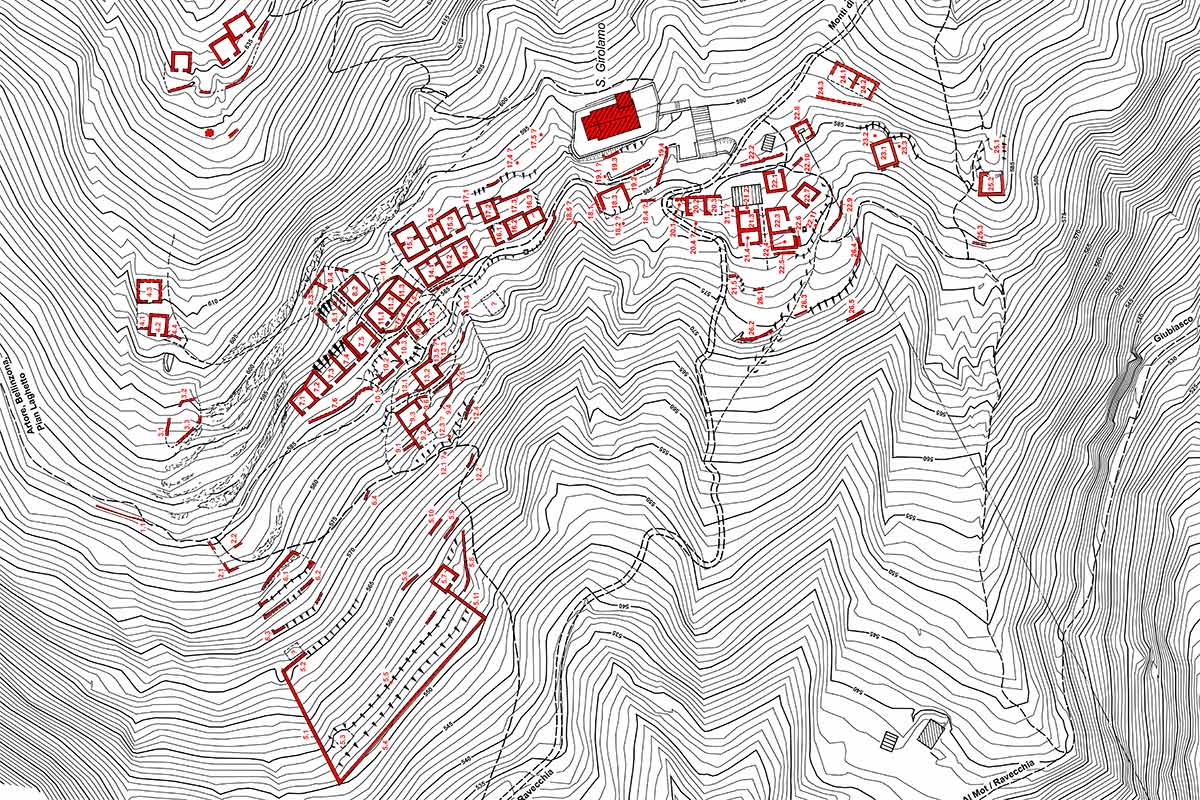

Prada, an ancient village also known as San Girolamo, is at an altitude of 577 metres above sea level, between the Dragonato and Guasta streams.

It lies in a small valley, sheltered from the northern wind, on the mountain above Ravecchia. The only way to get there is on foot, through a path that starts from Ravecchia, or from Serta, in Giubiasco's territory, where there used to be

another village which existed in the same period as Prada. Another option is from the Sasso Corbaro castle through Pian Laghetto.

It is unknown when the first inhabitants started living there; Prada probably already existed around the end of the 13th century if not earlier.

The reason why Prada was abandoned and when this occurred are unknown.

An urban legend blames Prada's depopulation on an epidemic of the plague dating from 1629 to 1630, known as "Federico Borromeo's plague", that is mentioned in Manzoni's "I promessi sposi" ("The Betrothed") and also swept through Milan six

months after it struck Ticino.

It is said that the village of Prada was used as a lazaretto, but there is no evidence to support this theory either.

When Rudolf Schinz, a protestant pastor, visited Ticino in 1770, he wrote in his chronicles about the houses in Prada, saying that they had been built in a hurry to give shelter to the population during the plague epidemic.

However, he doesn't specify which epidemic it was.

It should be noted that in 1770 Prada had already been abandoned for over a century.

One thing is certain: the houses in Prada are anything but built in a hurry and in fact they show signs that they were built with precision and care, using very strong lime mortar and carefully worked and set stones, as we can still see

to this day.

If the builders of Prada hadn't used such care, we would be facing much worse ruins.

The last records of people from Prada in the registries of the Brotherhood of the Blessed Sacrament, in the parish of San Biagio in Ravecchia, date back to about 1630-1640, just after the aforementioned epidemic.

Another theory, maybe the most reliable, is that Prada lost its population gradually due to a series of unknown causes.

Prada, along with Ravecchia, used to be part of the municipal territory of Bellinzona, like Montecarasso, Daro, Artore, and Pedemonte.

As such, Prada's inhabitants enjoyed the status of villagers, like those who lived within the confines of the walls or in the outskirts; in fact in 1430, Giovanni Zanolo from Prada was appointed as a representative for Ravecchia and Daro

in the town hall of Bellinzona.

In November of that same year, Zanolo also became the city's Procurator and Mayor. The list of members of the "Territorial Council" who had a seat between January 1629 and July 1631, during the "Borromeo" plague, include a Marietto del

Grando from Prada.

On the 5th of January 1498 the Council granted a subsidy to Prada's inhabitants for their existing church.

On the 12th of November 1523 a specific ruling established a perpetual benefit, under the patronage of the people of Prada, setting aside 60 "lire terzuole" every year to have a chaplain who would celebrate Mass on Sundays.

On the 9th of December 1583, Saint Carlo Borromeo visited Prada.

Accounts of his visit state that at that time there were 40 families in the village.

That meant a population of 140 to 200 people; Bellinzona, counted around 1200-1400 inhabitants in that year.

Prada, like most old villages in the Ticino valley, was situated at mid-height from the valley floor, as we can see with San Defendente in Sementina, San Bernardo Curzùtt in Monte Carasso, Sassa above Gorduno and Aragno above Arbedo, just

to mention a few in the neighbourhood of Bellinzona.

The river Ticino hadn't been yet tamed into its embankments, so people avoided building near the river due to the excessive risk of floods that occurred periodically and could wipe out entire villages.

Another reason was that in those times (the Middle Ages) the economy was based on agriculture and sheep farming, so people tried to take advantage of any patch of land that could be used to grow cereals, vines and for livestock

grazing.

For example, in 1457, the plain of Magadino was considered a beautiful location with wellsprings and still and running waters.

After the reclamation done at the beginning of the 20th century and the building of embankments for the river Ticino, the plain of Magadino also provided agricultural subsistence; however, it had been fairly valuable in the past as

well.

People could travel through it or go fishing and it was also a good place for livestock grazing.

Its unfortunate reputation as a swampy and diseased plain where unruly soldiers roamed is a myth that somewhat needs dispelling.

Going back to Prada, its houses were simple, with two rooms one on top of the other; both the house and the rooms had external access.

They had no cellars or chimneys.

Some of the doors had an arch, others had a stone lintel which resembled the arch-shaped ones with a hint of a rounding on the upper part.

A sculpted cross is always present on the stone lintel of the doors and in some cases of the small windows, but there never is a date.

Unfortunately only one of these lintels is still in its original location.

Four more have been found in the vicinity in the ground and are currently in the churchyard.

One lintel was found recently (2014) in the upper part of Prada, again bearing a carved cross.

As mentioned, the houses didn't have a chimney: the fire would be lit in a corner and a square opening in the wall measuring about 25 cm on each side was provided as a vent for the smoke.

Documents report the existence of a Lower Prada and an Upper Prada.

The latter (called by the natives "pra d'Zura") is a group of ruins located five minutes uphill from the church, on the path that leads to Monti di Ravecchia.

In addition to these two clusters, along the hill there are more remains of houses and walls that used to be part of farmhouses, evidence of the transfer of livestock.

Unfortunately the ruins of the village are slowly being hidden by the ground and the growing vegetation, but the first destruction was man's own doing, breaking down houses near the church to build the steeple in 1816, as already

mentioned in the specific chapter.

The same thing may have happened when the choir was built during the enlargement of the church around 1680 and again in the early 1900's, when the path to Monti di Ravecchia was built; not to mention the theft of stone lintels.

A census from the 1980's states that Prada had around fifty buildings between houses, stables and barns.

The inhabitants of Prada used to live off agriculture, viticulture and animal farming.

They used all the terraced land around the village; in fact one can still see the small walls they built to support these small fields.

There is a significant number of them in upper Prada, but villagers also used to go down to Ravecchia to tend to the fields.

One must consider that the territory going from Ravecchia to Prada wasn't how we see it today.

In medieval times the forest had not yet invaded the hilly territory, where vineyards were predominant.

Vineyards were very close to the homes of Prada.

In the sixteenth century one third of the usable land was reserved for vineyards. Barley, millet, and rye were also grown and were milled locally.

Chestnuts also were used as food.

The remarkable viticulture was due to the fact that families used to buy grains by selling the excess must, so they didn't have the hassle of growing the grains themselves and risking a poor harvest.

Products from sheep farming, such as milk, cheese, and butter, were also available and were produced also in higher pastures like Arbino.

In short, Prada's inhabitants, like in other villages in the valleys of Ticino, even at greater altitudes, were completely autonomous and self-sufficient.

Even after the village was abandoned, the parson of Ravecchia was required to celebrate twelve Holy Masses a year, four of which in prearranged holidays.

This practice continued until the end of the 19th century, when the masses were reduced to four and then two, as still occurs today, for Whit Monday and for Saint Rocco (celebrated on the second Sunday of August).

Until the 1950's, there used to be a procession that started from the chuch of San Biagio to celebrate Saint Rocco.

The ancient church was not as we see it now; it was smaller.

The choir was added around the end of the 17th century (1680-90).

The lunette depicting Saint Girolamo, above the choir window, bears the date 1686.

The steeple was built in 1816. These tangible marks show a particular fondness of Ravecchia's people for this place, although the village had already been abandoned by then.

Prada's church steeple we see today was built in 1816. It cost 993.13 Milanese lire and it was built by using the stones from the houses, as we can see from two carefully worked stones, one set in the south wall and one in the north one,

approximately halfway up the steeple.

These stones clearly show the hole where the tip of a bolt used to be inserted, indicating that they used to be part of the entrance to the ancient houses.

More of these stones can be found inside the steeple. Two bells were also bought in that same year.

In 1938, during the construction of the new St. John the Baptist hospital, a carved slab of stone was found bearing this inscription: Haec sacra turris edificata est a fundamentis anno Domini M.D.C.C.C.XVI, which means: "This holy tower

was built from its foundations in the year of our Lord 1816".

Today this slab is located on the internal wall of the entrance to the churchyard. According to reports from pastoral visits, before the current steeple was built there used to be a small bell-gable above the main entrance.

On the 18th of May 2010, while cutting down the shrubs growing amidst the ruins of the ancient village, two finely carved crescent-shaped stone lintels were found.

This was the first finding of lintels of this shape.

They used to be part of two rear entrances and bear no inscriptions.

In fact they were found within the perimeter of the only building that still had the main door lintel in its original place.

This lintel is triangular and bears a sculpted cross.

Late medieval paintings were discovered beneath a layer of plaster during the restoration of the choir murals in 2007.

Thanks to this final important specialistic work we were able to gain further important information on the history of the church.

As already mentioned, the choir that used to be where the altar now stands was added around 1680.

Therefore the church used to be smaller, ending at the triumphal arch, which also acted as an end wall.

Evidence of this is a small cross-shaped window, which is only visible from the attic of the church.

To know more about it, though, would require an archaeological exploration under the floor.

The altar was probably small, stood against the wall and was almost certainly decorated.

Indeed, remains of an architectural step can be seen along the lower internal margins of the intrados (on both sides).

A piece of painted plaster was found in the left intrados mortar that covered illustrations of characters of the Old Testament.

This piece used to be part of the aforementioned architectural step that connected the intrados to the original wall, subsequently demolished.

According to the restoration workers, this finding bears a fragment of a spiral decoration that could represent the "Tree of Jesse" and accompanied the figures depicted on the intrados (Christ's genealogy, from Isaiah's prophecy).

On half of the intrados, pointing towards the faithful, one can admire ten characters (busts of major and minor prophets, kings, ancestors of Christ).

Among these figures, Moses is unmistakable as he is depicted sporting a pair of horns.

Each one of these characters is accompanied by a cartouche that is hardly readable since the letters are almost completely gone.

Two other characters are present but are still hidden by plaster.

Probably there were no capitals originally, but only smooth and painted abutments.

Restoration workers can make a plausible comparison with the north apse (by the Seregnese workshop) of the church of Saint Ambrose in the town of Negrentino-Prugiasco.